I can’t believe how many years it’s been since I was first introduced to the FIRE movement. After reaching a 50% savings rate, I pretty much tapped out trying to increase this number further – and I think that was good for me – but now that I’m 2+ years into unemployment, I’ve realized something critical: those sexy FIRE tax hacks that were so appealing to me early on now sound annoying and pointless. Let me explain.

1. HSA Trickery

One strategy involves treating your HSA as an additional retirement account. You can do this by paying your “qualified medical expenses” out-of-pocket, saving the receipts, and then deducting them when the time is right. This allows you to keep your tax-free money in your HSA for as long as possible. If I remember it correctly, the idea was that by having boat loads of money in your HSA and not withdrawing anything from it, the compounding of the investments would be greater, so that when you deduct 20 years later (or whenever), it will have grown more and worked in your favor.

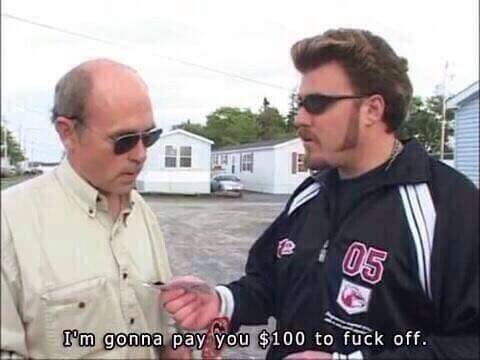

Why does this strategy deserve to go fuck itself? Because it’s a waste of your life trying to hold on to documentation like that, hoping one day to scrape an extra couple grand from your earnings. If you are a hyper-optimizer or a CPA, you might not mind the extra effort, but I think HSAs are great for health-related expenses, because they were designed to be. Treating them like a separate retirement account defeats the purpose. Besides, this strategy is only truly effective if you have tens of thousands of dollars in your HSA, in which case you’re already doing pretty well in the game of income, so those thousands you hope to earn don’t really mean much to you in the grand scheme of things. Besides, I would discourage anyone from hesitating to use their HSA for their health in the name of keeping the investment dollar amount high. Sure, the idea is to use out-of-pocket money instead, but people have a natural aversion to spending this on their health as well. If you need treatment, and you having the money in your HSA, just use it. It’s no good to you if you’re dead or beyond the point of treatment. What’s so wrong with using an HSA the way it was intended? Unless you just hate the government and want to find a clever way to way to stick it to the man (who is actually a collective of people who couldn’t care less).

2. Mega Backdoor Roth

First of all, this strategy was always a rare one, as you needed to be a part of a 401k plan that allowed it; you also needed to be earning boatloads of money to take advantage of it. If I remember correctly, the idea was that there’s a limit to how much you can invest in a Roth IRA each year, but there’s some shenanigans where you can contribute post-tax dollars to a 401k, then reconstitute it as Roth money later. I don’t remember all of the details. This was long thought to be the holy grail of tax hacks, but again, hardly anybody is able to do it. It sounds like a nightmare to file, which opens you up to a different form of risk, and therein lies the crux of why I don’t care for it anymore.

It sounds great, but it requires you to be earning a stupid-high income to pull off. It’s one strategy that actually works fairly well if you have the ability to do it, but again, I’ve encountered some of that tax work, and it doesn’t sound fun. Beyond maxing other accounts out, there’s just more to life that trying to perfectly fill these buckets.

3. Overemphasis on the Traditional 401k and Traditional IRA

There was an extremely popular post by one of the main FIRE bloggers that broke down the math of why investing in a Traditional 401k or Traditional IRA has higher returns than investing in a Roth 401k or Roth IRA. It’s a cute idea; I wouldn’t fault anybody for following it. The idea is that money invested before paying federal and state taxes can grow larger over time than money invested after paying federal and state taxes, and while that may be true statistically, it also assumes that you live long enough to enjoy the benefit, and it works better the longer you go before withdrawing. However, what broke my heart late last year was realizing that every $1,000 I withdrew from my traditional IRA cost me 10% as an early-withdrawal penalty, 22% as federal tax, and 4.4% as state tax. Paying 10% or 15% for federal wasn’t so terrible, but my total “income” for the year just pushed me past those brackets into the 22% range, and my goodness does it hurt when you start paying taxes at that level. You end up almost paying $400 for every $1,000 you withdraw: let that sink in. Mind you, you pay the tax one way or the other, and you can avoid the 10% penalty by not withdrawing until retirement age (and meeting the right requirements, etc.), but I now think to myself how beautiful it would be to have $100k or $200k in Roth IRA contributions, how few shits you would have to give about any of this, and how easy it would be to earn some money on the side that fits within the standard deduction (which essentially means you wouldn’t have to worry about paying taxes on it).

[Remembering, of course, that Roth IRA growth is taxed differently, but Roth IRA contributions are part of the basis you can withdraw from. It’s interesting. Roth 401ks are a little different from this, as withdrawals are pro rata, so you always pay some tax. I think converting a Roth 401k to a Roth IRA takes 5 years before the rules fully switch over? I should research that again]

I don’t know man, that’s my fantasy at this point. Sure, going Roth might not be “optimal”, but if it means you can take a year off, few shits given, and tax season takes you all of 1 or 2 hours to file, that sounds fantastic to me. Again, if you’re earning enough to even set money aside, you can already count your blessings and avoid the pain of getting fancy.

Conclusion

At one time, I was wholly focused on early retirement, but this whole career shift and everything I feel God has been trying to communicate have really shown me that this ought not to be my highest priority. It made sense before, but I now have some additional direction in life, such that early retirement doesn’t have the same value it used to. I’ve also come to accept I’ve already been so fortunate to earn the money I have, that it’s almost an act of sheer appreciation to stop taking these strategies so seriously: they are unlikely to contribute significantly to my future above and beyond what has already been done for me. The money I’ve spent has had an enormous financial opportunity cost, but I suspect there was an even greater costs to putzing around in a job I didn’t care about, too. I think it’s Jordan Peterson who says that while activity has a cost, so does inactivity.

Strangely enough, too, pre-tax money is more sensitive to market fluctuations, since you have to account for the extra that needs to be withdrawn in order to cover taxes. And for those who haven’t had the misfortune of learning the nuances of crap like this, it’s tough to beat the power and ease of the humble Roth IRA.